Originally prepared by: Brian Beatty

Revised:

(back to top)

Part 1 – The Cognitive Elite

Part 2 – IQ and Social Problems

Part 3 – IQ and Race

Part 4 – IQ and Social Policy

On the genetic nature of IQ

On pervasive disingenuousness

On social policy

On faulty conclusions

On divisive arguments

On social policy

Concluding comments

On the subject of evidence sources

On statistical abuse

On the relationship between poverty and intelligence

On affirmative action

On the divisiveness of The Bell Curve’s argument

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

CONTENT

The Bell Curve begins with fundamental and important assumptions, makes assertions (supported by the author’s evidence), draws conclusions based on statistical analysis of the evidentiary data, and concludes with wide-ranging recommendations for national policy-makers to follow. The authors state that their main motive is, ” the quest for human dignity.” (p. 551). Their concluding paragraph seems to support this motive:

“Inequality of endowments, including intelligence, is a reality. Trying to pretend that inequality does not really exist has led to disaster. Trying to eradicate inequality with artificially manufactured outcomes has led to disaster. It is time for America once again to try living with inequality, as life is lived: understanding that each human being has strengths and weaknesses, qualities we admire and qualities we do not admire, competencies and incompetencies, assets and debits; that the success of each human life is not measured externally but internally; that all of the rewards we can confer on each other, the most precious is a place as a valued fellow citizen.” (pp 551-552)

The Bell Curve, in its introduction, begins with a brief description of the history of intelligence theory and recent developments in intelligence thought and testing, through the eyes of the authors. The introduction concludes with six important assumptions that the authors build much of the Bell Curve’s case upon. These six assumptions regarding the validity of “classical” cognitive testing techniques include:

-

- There is such a difference as a general factor of cognitive ability on which human beings differ.

- All standardized test of academic aptitude or achievement measure this general factor to some degree, but IQ tests expressly designed for that purpose measure it most accurately.

- IQ scores match, to a first degree, whatever it is that people mean when they use the word intelligent, or smart in ordinary language.

- IQ scores are stable, although not perfectly so, over much of a person’s life.

- Properly administered IQ tests are not demonstrably biased against social, economic, ethnic, or racial groups.

- Cognitive ability is substantially heritable, apparently no less than 40 percent and no more than 80 percent.

The authors proceed to explain, using classical cognitive test results primarily, to explain how lower levels of measured intelligence impact an individual’s, or indeed an entire class or group of individual’s life in American society. The rest of the book is divided into four major parts.

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

- Poverty – Low IQ is a strong precursor of poverty, even more so than the socioeconomic conditions in which people grow up.

- Schooling – Low IQ raises the likelihood of dropping out of school before completing high school, and decreases the likelihood of attaining a college degree.

- Unemployment, Idleness and Injury – Low IQ is associated with persons who are unemployed, injured often, or idle (removed themselves from the workforce).

- Family Matters – Low IQ correlates with high rates of divorce, lower rates of marriage, and higher rates of illegitimate births,

- Welfare Dependency – Low IQ increases the chances of chronic welfare dependency.

- Parenting – Low IQ of mothers correlates with low birth weight babies, a child’s poor motor skill and social development, and children’s behavioral problems from age 4 and up.

- Crime – Low IQ increases the risk of criminal behavior.

- Civility and Citizenship – Low IQ people vote least and care least about political issues.

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

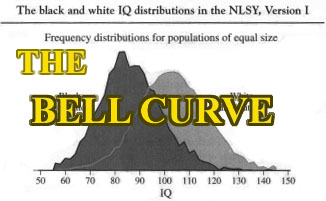

- Ethnic Differences in Cognitive Ability – East Asians typically earn higher IQ scores than white Americans, especially in the verbal intelligence areas. African-Americans typically earn IQ scores one full standard deviation below those of white Americans. The IQ difference between African-Americans and whites remains at all levels of socioeconomic status (SES), and is even more pronounced at higher levels of SES. Recent narrowing of the average IQ gap between black and white Americans (about 3 IQ points) is attributed to a lessening of low black scores and not an overall improvement in black scores on average. The debate over genes versus environment influences on the race IQ gap is acknowledged.

- The Demography of Intelligence – Mounting evidence indicates that demographic trends are exerting downward pressure on the distribution of cognitive ability in the United States and that the pressures are strong enough to have social consequences. Birth rates among highly educated women are falling faster than those of low IQ women. The IQ of the average immigrant of today is 95, lower than the national average, but more importantly the new immigrants are less brave, less hard working, less imaginative, and less self-starting than many of the immigrant groups of the past.

- Social Behavior and the Prevalence of Low Cognitive Ability – For most of the worst social problems of our time, the people who have the problem are heavily concentrated in the lower portion of the cognitive ability spectrum. Solutions designed to solve or mitigate any of these problems must accommodate, even be focused towards, the low cognitive ability profile if they are to have any hope of succeeding.

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

- Raising Cognitive Ability – If it were possible to significantly, consistently, and affordably raise intelligence, many of the negative consequences of societal low IQ could be mitigated or removed. However, historical attempts to raise IQ using nutritional programs, additional formal schooling, and government preschool programs (such as Head Start) have proven to have little if any lasting impact on intelligence as measured by IQ tests. The one intervention that has consistently worked to raise intelligence is adoption form a bad family environment into a good one. The authors recommend that children born to single mothers with low cognitive ability be voluntarily given up for adoption.

- The Leveling of American Education – The average American school child has not suffered from recent declines in overall school system measurements. Indeed, the focus of American public education has shifted more and more towards educating the average and below-average child to the exclusion of gifted children. Among the most gifted students, SAT scores have been falling since the mid -1960ís. No more than one-tenth of one percent of federal education spending is targeted towards the gifted students. As American education has been “dumbed down” to accommodate the average and below average students, the gifted students have been allowed to slide by without developing their true potential. The authors recommend that some federal education funds be shifted from disadvantaged programs to gifted programs, and that the federal government encourage parental choice in education through voucher programs, public school choice programs, or tax credits for education. A final recommendation is for educators to once again view as one of the chief purposes of our educational system to educate the gifted because the future of society depends on them, an education that fosters wisdom and virtue through the ideal of the “educated man”.

- Affirmative Action in Higher Education – The edge given to minority applicants to college and graduate school is an extremely large advantage that puts them in a separate admissions process. Asians are a conspicuously unprotected minority due in large part to their above average intelligence scores. The cost of affirmative action in higher education includes the psychological consequences of students admitted under affirmative action programs, at lower cognitive ability levels, being seen as a low proportion of the overall student population, but a high proportion of the students doing poorly in school. This can lead to increased racial animosity and the high black dropout rate on American campuses. The authors recommend a color-blind affirmative action, giving preference to members of disadvantaged groups when qualifications are similar.

- Affirmative Action in the Workplace – Affirmative action programs in the workplace have had some impact, on some kinds of jobs, in some settings, during the 1960ís and 70ís, but have not had the decisive impact that is commonly asserted in political rhetoric. action does produce large racial discrepancies in job performance in a given workplace. Blacks have been overrepresented in white collar and professional occupations relative to the number of candidates in the IQ range from which these jobs are usually filled. The data suggest that aggressive affirmative action does produce large racial discrepancies in job performance in a given workplace. The authors recommend a color-blind affirmative action, giving preference to members of disadvantaged groups when qualifications are similar.

- The Way We are Headed – Three significant trends have emerged that, left unchecked, will lead the U.S. toward something resembling a caste society. These trends are: 1) An increasingly isolated cognitive elite, 2) A merging of the cognitive elite with the affluent, and 3) A deteriorating quality of life for people at the bottom end of the cognitive ability distribution. The authors see the continued polarization of society with the underclass anchored at the bottom, and the cognitive elite anchored at the top, restructuring the rules of society so that it becomes harder and harder for them to lose. The author’s denouement of their prognosis is the coming of the “custodial state – an expanded welfare state for the underclass that also keeps it out from underfoot”. The custodial state will have the following consequences: 1) Childcare in the inner city will become primarily the responsibility of the state. 2) The homeless will vanish. 3) Strict policing and custodial responses to crime will become more acceptable and widespread. 4) The underclass will become even more concentrated spatially than it is today. 5) The underclass will grow. 6) Social budgets and measures for social control will become still more centralized. 7) Racism will reemerge in a new and more virulent form.

- A Place for Everyone – In order to avoid the pessimistic custodial state conceptualized in the previous chapter, the authors propose a different scenario for American society in this chapter. The foundation to this alternative (more positive) scenario is the rethinking of equality and inequality.

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

CRITICISMS

The Bell Curve has inspired a literal mountain of response. A good summary of the critical response to The Bell Curve can be found in the book, The Bell Curve Debate, edited by Russell Jacoby and Naomi Glauberman (1995). The following sections are excerpted from The Bell Curve Debate:

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

Stephen Jay Gould is a professor of zoology at Harvard University; he is author of The Mismeasure of Man, Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes, and many other works.

His article originally appeared in The New Yorker, November 28, 1994, entitled “Curveball.”

The Bell Curve, by Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, subtitled Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life, provides a superb and unusual opportunity to gain insight into the meaning of experiment as a method in science. The primary desideratum in all experiments is reduction of confusing variables: we bring all the buzzing and blooming confusion of the external world into our laboratories and, holding all else constant in our artificial simplicity, try to vary just one potential factor at a time. But many subjects defy the use of such an experimental method particularly most social phenomena because importation into the laboratory destroys the subject of the investigation, and then we must yearn for simplifying guides in nature. If the external world occasionally obliges by holding some crucial factors constant for us, we can only offer thanks for this natural boost to understanding. (p. 3)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

The Bell Curve rests on two distinctly different but sequential arguments, which together encompass the classic corpus of biological determinism as a social philosophy. The first argument rehashes the tenets of social Darwinism as it was originally constituted. Social Darwinism has often been used as a general term for any evolutionary argument about the biological basis of human differences, but the initial nineteenth century meaning referred to a specific theory of class stratification within industrial societies, and particularly to the idea that there was a permanently poor underclass consisting of genetically inferior people who had precipitated down into their inevitable fate. The theory arose from a paradox of egalitarianism: as long as people remain on top of the social heap by accident of a noble name or parental wealth, and as long as members of despised castes cannot rise no matter what their talents, social stratification will not reflect intellectual merit, and brilliance will be distributed across all classes; but when true equality of opportunity is attained, smart people rise and the lower classes become rigid, retaining only the intellectually incompetent.This argument has attracted a variety of twentieth-century champions, including the Stanford psychologist Lewis M. Terman, who imported Alfred Binet’s original test from France, developed the Stanford-Binet IQ test, and gave a hereditarian interpretation to the results (one that Binet had vigorously rejected in developing this style of test); Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yevv of Singapore, who tried to institute a eugenics program of rewarding well-educated women for higher birth rates; and Richard Herrnstein, a co-author of The Bell Curve and also the author of a 1971 Atlantic Monthly article that presented the same argument without the documentation. The general claim is neither uninteresting nor illogical, but it does require the validity of four shaky premises, all asserted (but hardly discussed or defended) by Herrnstein and Murray. Intelligence, in their formulation, must be depictable as a single number, capable of ranking people in linear order, genetically based, and effectively immutable. If any of these premises are false, their entire argument collapses. For example, if all are true except immutability, then programs for early intervention in education might work to boost IQ permanently, just as a pair of eyeglasses may correct a genetic defect in vision. The central argument of The Bell Curve fails because most of the premises are false. (pp 4-5)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

Herrnstein and Murray’s second claim, the lightning rod for most commentary, extends the argument for innate cognitive stratification to a claim that racial differences in IQ are mostly determined by genetic causes small differences for Asian superiority over Caucasian, but large for Caucasians over people of African descent. This argument is as old as the study of race, and is almost surely fallacious. The last generation’s discussion centered on Arthur Jensen’s 1980 book Bias in Mental Testing (far more elaborate and varied than anything presented in The Bell Curve, and therefore still a better source for grasping the argument and its problems), and on the cranky advocacy of William Shockley, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist. The central fallacy in using the substantial heritability of within-group IQ (among whites, for example) as an explanation of average differences between groups (whites versus blacks, for example) is now well known and acknowledged by all, including Herrnstein and Murray, but deserves a restatement by example. Take a trait that is far more heritable than anyone has ever claimed IQ to be but is politically uncontroversial body height. Suppose that I measure the heights of adult males in a poor Indian village beset with nutritional deprivation, and suppose the average height of adult males is five feet six inches. Heritability within the village is high, which is to say that tall fathers (they may average five feet eight inches) tend to have tall sons, while short fathers (five feet four inches on average) tend to have short sons. But this high heritability within the village does not mean that better nutrition might not raise average height to five feet ten inches in a few generations. Similarly, the well-documented fifteen-point average difference in IQ between blacks and whites in America, with substantial heritability of IQ in family lines within each group, permits no automatic conclusion that truly equal opportunity might not raise the black average enough to equal or surpass the white mean. (p. 5)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

On pervasive disingenuousness:

Disturbing as I find the anachronism of The Bell Curve, I am even more distressed by its pervasive disingenuousness. The authors omit facts, misuse statistical methods, and seem unwilling to admit the consequences of their own words. (p. 6)Nothing in The Bell Curve angered me more than the authors’ failure to supply any justification for their central claim, the sine qua non of their entire argument: that the number known as g, the celebrated “general factor” of intelligence, first identified by the British psychologist Charles Spearman, in I904, captures a real property in the head. Murray and Herrnstein simply declare that the issue has been decided, as in this passage from their 1970 Republic article: “Among the experts, it is by now beyond much technical dispute that there is such a thing as a general factor of cognitive ability on which human beings differ and that this general factor is measured reasonably well by a variety of standardized tests, best of all by IQ tests designed for that purpose.” Such a statement represents extraordinary obfuscation, achievable only if one takes “expert” to mean “that group of psychometricians working in the tradition of g and its avatar IQ.” The authors even admit that there are three major schools of psychometric interpretation and that only one supports their view of g and IQ. (p. 8)

But this issue cannot be decided, or even understood, without discussing the key and only rationale that has maintained g since Spearman invented it: factor analysis. The fact that Herrnstein and Murray barely mention the factor-analytic argument forms a central indictment of The Bell Curve and is an illustration of its vacuousness. How can the authors base an 800-page book on a claim for the reality of IQ as measuring a genuine, and largely genetic, general cognitive ability and then hardly discuss, either pro or con, the theoretical basis for their certainty? (p. 8)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

Like so many conservative ideologues who rail against the largely bogus ogre of suffocating political correctness, Herrnstein and Murray claim that they only want a hearing for unpopular views so that truth will out. And here, for once, I agree entirely. As a card carrying First Amendment (near) absolutist, I applaud the publication of unpopular views that some people consider dangerous. I am delighted that The Bell Curve was written so that its errors could be exposed, for Herrnstein and Murray are right to point out the difference between public and private agendas on race, and we must struggle to make an impact on the private agendas as well. But The Bell Curve is scarcely an academic treatise in social theory and population genetics. It is a manifesto of conservative ideology; the book’s inadequate and biased treatment of data displays its primary purpose advocacy. The text evokes the dreary and scary drumbeat of claims associated with conservative think tanks: reduction or elimination of welfare, ending or sharply curtailing affirmative action in schools and workplaces, cutting back Head Start and other forms of preschool education, trimming programs for the slowest learners and applying those funds to the gifted. (I would love to see more attention paid to talented students, but not at this cruel price.) (p. 12)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

However, if Herrnstein and Murray are wrong, and IQ represents not an immutable thing in the head, grading human beings on a single scale of general capacity with large numbers of custodial incompetents at the bottom, then the model that generates their gloomy vision collapses, and the wonderful variousness of human abilities, properly nurtured, reemerges. We must fight the doctrine of The Bell Curve both because it is wrong and because it will, if activated, cut off all possibility of proper nurturance for everyone’s intelligence. Of course, we cannot all be rocket scientists or brain surgeons, but those who can’t might be rock musicians or professional athletes (and gain far more social prestige and salary thereby), while others will indeed serve by standing and waiting. (p. 13)I closed my chapter in The Mismeasure of Man on the unreality of g and the fallacy of regarding intelligence as a single-scaled, innate thing in the head with a marvellous quotation from John Stuart Mill, well worth repeating: The tendency has always been strong to believe that whatever received a name must be an entity or being, having an independent existence of its own. And if no real entity answering to the name could be found, men did not for that reason suppose that none existed, but imagined that it was something particularly abstruse and mysterious. (p. 13)

How strange that we would let a single and false number divide us, when evolution has united all people in the recency of our common ancestry thus undergirding with a shared humanity that infinite variety which custom can never stale. E pluribus unum. (p. 13)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

The Bell Curve is a strange work. Some of the analysis and a good deal of the tone are reasonable. Yet the science in the book was questionable when it was proposed a century ago, and it has now been completely supplanted by the development of the cognitive sciences and neurosciences. The policy recommendations of the book are also exotic, neither following from the analyses nor justified on their own. (p. 61)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

… I became increasingly disturbed as I read and reread this 800 page work. I gradually realized I was encountering a style of thought previously unknown to me: scholarly brinkmanship. Whether concerning an issue of science, policy, or rhetoric, the authors come dangerously close to embracing the most extreme positions, yet in the end shy away from doing so. Discussing scientific work on intelligence, they never quite say that intelligence is all important and tied to one’s genes; yet they signal that this is their belief and that readers ought to embrace the same conclusions. Discussing policy, they never quite say that affirmative action should be totally abandoned or that childbearing or immigration by those with low IQs should be curbed; yet they signal their sympathy for these options and intimate that readers ought to consider these possibilities. Finally, the rhetoric of the book encourages readers to identify with the IQ elite and to distance themselves from the dispossessed in what amounts to an invitation to class warfare. Scholarly brinkmanship encourages the reader to draw the strongest conclusions, while allowing the authors to disavow this intention. (p. 63)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the book is its rhetorical stance. This is one of the most stylistically divisive books that I have ever read. Despite occasional avowals of regret and the few utopian pages at the end, Herrnstein and Murray set up an us/them dichotomy that eventually culminates in an us-against-them opposition. (p. 70)Who are “we” ? Well, we are the people who went to Harvard (as the jacket credits both of the authors) or attended similar colleges and read books like this. We are the smart, the rich, the powerful, the worriers. (p. 70)

Why is this so singularly off-putting? I would have thought it unnecessary to say, but if people as psychometrically smart as Messrs. Herrnstein and Murray did not “get it,” it is safer to be explicit. High IQ doesn’t make a person one whit better than anybody else. And if we are to have any chance of a civil and humane society, we had better avoid the smug self-satisfaction of an elite that reeks of arrogance and condescension. (p. 71)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

Though there are seven appendices, spanning over 100 pages, and nearly 200 pages of footnotes, bibliography, and index, one element is notably missing from this tome: a report on any program of social intervention that works. For example, Herrnstein and Murray never mention Lisbeth Schorr’s Within Our Reach: Breaking the Cycle of Disadvantage, a book that was prompted in part by Losing Ground. Schorr chronicles a number of social programs that have made a genuine difference in education, child health service, family planning, and other lightning rod areas of our society. And to the ranks of the programs chronicled in Schorr’s book, many new names can now be added. Those who have launched Interfaith Educational Agencies, City Year, Teach for America, Jobs for the Future, and hundreds of other service agencies have not succumbed to the sense of futility and abandonment of the poor that the Herrnstein and Murray book promotes. (p. 71)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

It is callous to write a work that casts earlier attempts to help the disadvantaged in the least favorable light, strongly suggests that nothing positive can be done in the present climate, contributes to an us-against-them mentality, and then posits a miraculous cure. High intelligence and high creativity are desirable. But unless they are linked to some kind of a moral compass, their possessors might best be consigned to an island of glass bead game players, with no access to the mainland. (p. 72)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

His article is an expanded version of a review that appeared in Scientific American February 1995.

“The publicity barrage with which the book was launched might suggest that The Bell Curve has something new to say; it doesn’t. The authors, in this most recent eruption of the crude biological determinism that permeates the history of IQ testing, assert that scientific evidence demonstrates the existence of genetically determined differences in intelligence among social classes and races. They cite some 1,OOO references from the social and biological sciences, and make a number of suggestions for changing social policies. The pretense is made that there is some logical, “scientific” connection between evidence culled from those cited sources and the authors’ policy recommendations. Those policies would not be necessary or humane even if the cited evidence were valid. But I want to concentrate on what I regard as two disastrous failings of the book. First, the caliber of the data cited by Herrnstein and Murray is, at many critical points, pathetic and their citations of those weak data are often inaccurate. Second, their failure to distinguish between correlation and causation repeatedly leads Herrnstein and Murray to draw invalid conclusions.” (pp 81-82)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

On the subject of evidence sources:

“Herrnstein and Murray rely heavily upon the work of Richard Lynn, whom they described as “a leading scholar of racial and ethnic differences”, from whose advice they have “benefited especially”. ““I will not mince words. Lynn’s distortions and misrepresentations of the data constitute a truly venomous racism, combined with scandalous disregard for scientific objectivity. But to anybody familiar with Lynn’s work and background, this comes as no surprise. Lynn is widely known to be an associate editor of the vulgarly racist journal Mankind Quarterly; his 1991 paper comparing the intelligence of “Negroids” and “Negroid-Caucasoid hybrids” appeared in its pages. He is a major recipient of financial support from the nativist and eugenically oriented Pioneer Fund. It is a matter of shame and disgrace that two eminent social scientists, fully aware of the sensitivity of the issues they address, take as their scientific tutor Richard Lynn, and accept uncritically his surveys of research. Murray, in a newspaper interview, asserted that he and Herrnstein had not inquired about the “antecedents” of the research they cite. “We used studies that exclusively, to my knowledge, meet the tests of scholarship.” What tests of scholarship?” (p. 86)

Herrnstein and Murray cite the work of Arthur Jensen on reaction time testing and racial differences Kamin comments:

“The cited Jensen paper (1993) presents data for blacks and whites, for both reaction and movement time, for three different “elementary cognitive tasks.” The results are not, despite Herrnstein and Murray’s contention, “consistent.” Blacks are reported to have faster movement times on only two of the three tasks; and they have faster reaction times than whites on one task, “choice reaction time.” Simple reaction time merely requires the subject to respond as quickly as possible to a given stimulus each time it occurs. Choice reaction time requires him/her to react differently to various stimuli as they are presented in an unpredictable order. Thus it is said to be more cognitively complex, and to require more processing, than simple reaction time. When Jensen first used reaction time in 1975 as a measure of racial differences in intelligence, he claimed that blacks and whites did not differ in simple reaction time, but that whites, with their higher intelligence, were faster in choice reaction time. He repeated this ludicrous claim incessantly, while refusing to make the raw data of his study available for inspection. Then, in a subsequent 1984 paper, he was unable to repeat his earlier finding in a new study described as “inexplicably inconsistent” with his 1975 results. Now, in the still newer 1993 study cited by Herrnstein and Murray, Jensen reports as “an apparent anomaly” that (once again!) blacks are slightly faster in choice reaction time than whites. Those swift couriers, Herrnstein and Murray, are not stayed from their appointed rounds by anomalies and inconsistencies. Two out of three is not conclusive. Why not make the series three out of five?”(p. 88)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

“The confusion between correlation and causation permeates the largest section of The Bell Curve, an interminable series of analyses of data gathered from the National Longitudinal Survey of Labor Market Experience of Youth (NLSY). Those data, not surprisingly, indicate that there is an association within each race between IQ and socioeconomic status (SES). Herrnstein and Murray labor mightily in an effort to show that low IQ is the cause of low SES, and not vice versa. Their argument is decked out in all the trappings of science a veritable barrage of charts, graphs, tables, appendices, and appeals to statistical techniques that are unknown to many readers. But on close examination, this scientific emperor is wearing no clothes.” (p. 90)“Herrnstein and Murray pick over these data, trying to show that it is overwhelmingly IQ not childhood or adult SES that determines worldly success and the moral praiseworthiness of one’s social behaviors. But their dismissal of SES as a major factor rests ultimately on the self-reports of youngsters. That is not an entirely firm basis. I do not want to suggest that such self-reports are entirely unrelated to reality. We know, after all, that children from differing social class backgrounds do indeed differ in IQ; and in the NLSY study the young peoples’ self-reports are correlated with the objective facts of their IQ scores. But comparing the predictive value of those self-reports to that of quantitative test scores is playing with loaded dice.” (p. 91)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

On the relationship between poverty and intelligence:

“The core of the Herrnstein-Murray message is phrased with a beguiling simplicity: “Putting it all together, success and failure in the American economy, and all that goes with it, are increasingly a matter of the genes that people inherit.” The “increasing value of intelligence in the marketplace” brings “prosperity for those lucky enough to be intelligent.” Income is a “family trait” because IQ, “a major predictor of income, passes on sufficiently from one generation to the next to constrain economic mobility.” Those at the bottom of the economic heap were unlucky when the IQ genes were passed out, and will remain there.” (p. 91)“There are a number of criticisms to be made of the ways in which Herrnstein and Murray analyze the data, and especially so when they later extend their analyses to include black and Hispanic youth. But for argument’s sake, let us now suppose that their analyses are appropriate and accurate. We can also grant that, rightly or wrongly, disproportionate salaries and wealth accrue to those with high IQ scores. What then do the Herrnstein-Murray analyses tell us?” (p. 92)

“The SES of one’s parents cannot in any direct sense “cause” one’s IQ to be high or low. Family income, even if accurately reported, obviously cannot directly determine a child’s performance on an IQ test. But income and the other components of an SES index can serve as rough indicators of the rearing environment to which a child has been exposed. With exceptions, a child of a well-to-do broker is likely to be exposed to book-learning earlier and more intensively than a child of a laborer. And extensive practice at reading and calculating does affect, very directly, one’s IQ score. That is one plausible way of interpreting the statistical link between parental SES and a child’s IQ.” (p. 92)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

“The Bell Curve, near its closing tail, contains two chapters concerned with affirmative action, in higher education and in the workplace. To read those chapters is to hear the second shoe drop. The rest of the book, I believe, was written merely as a prelude to its assault on affirmative action. The vigor of the attack is astonishing.” (p. 98)“Now, at long last, Herrnstein and Murray let it all hang out: “affirmative action, in education and the workplace alike, is leaking a poison into the American soul.” Having examined the American condition at the close of the twentieth century, these two philosopher-kings conclude, “It is time for America once again to try living with inequality, as life is lived….” This kind of sentiment, I imagine, lay behind the conclusion of New York Times columnist Bob Herbert that “the book is just a genteel way of calling somebody a nigger.” Herbert is right. The book has nothing to do with science.” (p. 99)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

“That psychometric tradition of heads-I-win-tails-you-lose has been carried forward intact by Herrnstein and Murray. They acknowledge that James Flynn has demonstrated that across the world intelligence as measured by IQ tests has been increasing dramatically over time. Thus an average contemporary youngster, taking an IQ test that had been standardized twenty years ago, would have a considerably higher than average IQ score. Perhaps, Herrnstein and Murray suggest, “Improved health, education, and childhood interventions may hide the demographic effects…. Whatever good things we can accomplish with changes in the environment would be that much more effective if they did not have to fight a demographic head wind.” Their conviction that “something worth worrying about is happening to the cognitive capital of the country” is unshakable. Imagine the heights that America could scale if a Ph.D. in social science were a prerequisite for the production of offspring! With environmental advantages working exclusively upon such splendid raw material, no head winds would delay our arrival at Utopia. And we would sell more autos to the Japanese.” (p. 105)

“That is the kind of brave new world toward which The Bell Curve points. Whether or not our country moves in that direction depends upon our politics, not upon science. To pretend, as Herrnstein and Murray do, that the 1,000-odd items in their bibliography provide a “scientific” basis for their reactionary politics may be a clever political tactic, but it is a disservice to and abuse of science. That should be clear even to those scientists (I am not one of them) who are comfortable with Herrnstein and Murray’s politics. We owe it to our fellow citizens to explain that the reception of their book had nothing to do either with its scientific merit or the novelty of its message.” (p. 105)

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Herrnstein, R. J. and Murray, C., (1994). The Bell Curve. New York: The Free Press.

Jacoby, R. and Glauberman, N., eds, (1995). The Bell Curve Debate. Times Books.

TOP | OUTLINE | CONTENT | CRITICISMS

- Please feel free to contact us with issues, questions, and contributions that you feel would help others using this site as a resource.